TL:DR

I scrape the number of search engine results for every possible 3 and 4 letter combination in the English alphabet, and try to figure out which sequences might be ‘hidden gems’ that are not already popularized by society.

Introduction

Tidings! I write from the mountains of Sedona, Arizona. I’m here with a childhood friend, and took two weeks off from the city for a mental reset.

As most do in November, I’m planning out a lot of things for 2024; I’m coming up with lots of names for projects, and I’m thinking about how to make them ‘roll off the tongue’, persay. Every time I come up with a name that sounds pleasant, I google it and find that it’s already taken (or worse, trademarked) by an organization, product, or idea.

It’s annoying! So, I began to think about ways to generate names that are unique. And, well, the first step in doing that is to figure out which names (or, for the rest of the article, I’ll call them sequences) are already taken.

When thinking about how to do this, a small, relatively unknown element of a Google search reuslts page came to mind:

“About 63,500,000 results”.

This obviously lacks have a high degree of precision, but thankfully we don’t need any significant figures for this endeavour. I’m merely trying to see, within the relative distribution of all sequences, which sequences might be ‘hidden gems’ that are not already popularized by society.

Methodology

Preface: If you want to follow along, all code is available at GitHub.

The Backbone

Generating all possible n-length sequences

I first wrote a simple bash script to generate all possible n-length sequences of the English alphabet. This script takes in a length n and an output file, and writes all possible sequences to the output file.

#!/bin/bash # A script, reformed, to generate and count the sequences of the English alphabet. generate_combinations() { # Within the labyrinth of recursion, we conjure sequences anew. if [ $2 -eq 0 ]; then echo "$1" else for letter in {a..z}; do generate_combinations "$1$letter" $(($2 - 1)) done fi } # The seeker must provide the length, n, as a numeral. if [ $# -eq 0 ] || ! [[ $1 =~ ^[0-9]+$ ]]; then echo "Pray, provide the sequence length as an integer, true and whole." exit 1 fi # The seeker must provide a file to write the combinations to. if [ $# -eq 1 ]; then echo "Pray, provide a file to write the combinations to." exit 1 fi # Let the script unleash its magic, weaving the alphabetic sequences. generate_combinations "" $1 >> $2 # The count of combinations, a simple calculation: 26^n. total_combinations=$((26**$1)) # Reveal to the seeker the grand enumeration of combinations. echo "Total combinations for length $1: $total_combinations"

Fetching the number of search results for a sequence

Then, I wrote a script to fetch the number of search results for an arbitrary sequence. An important note here is that I wrap each sequence in double quotes, so that the search engine only returns results for the exact sequence. This script takes in a sequence, runs a curl request to the search engine on that sequence, and then parses the resultant HTML with htmlq, a command line tool for parsing html. I identified which class to isolate via a simple inspection of the HTML with the Google Chrome inspector offered in the developer tools.

Fetching the number of search results for all sequences in a file

And, finally, I wrote a script to fetch the number of results in batch for all sequences present in a file. Each sequence gets it’s own line in the file, and the script iterates through each line, calling the previous script to fetch the number of results for that sequence.

Hiccups

Google.

So, I immediately thought to use Google due to their 83% market share Statista of the search engine market. However, the most prominent barrier to using Google arose immediately: the company aggressively blocks automated requests. I was able to run about 100 requests before Google temporarily blocked my IP address. I’m not a web scraping expert, so I wasn’t sure how to get around this without thousands of proxies (which I don’t have).

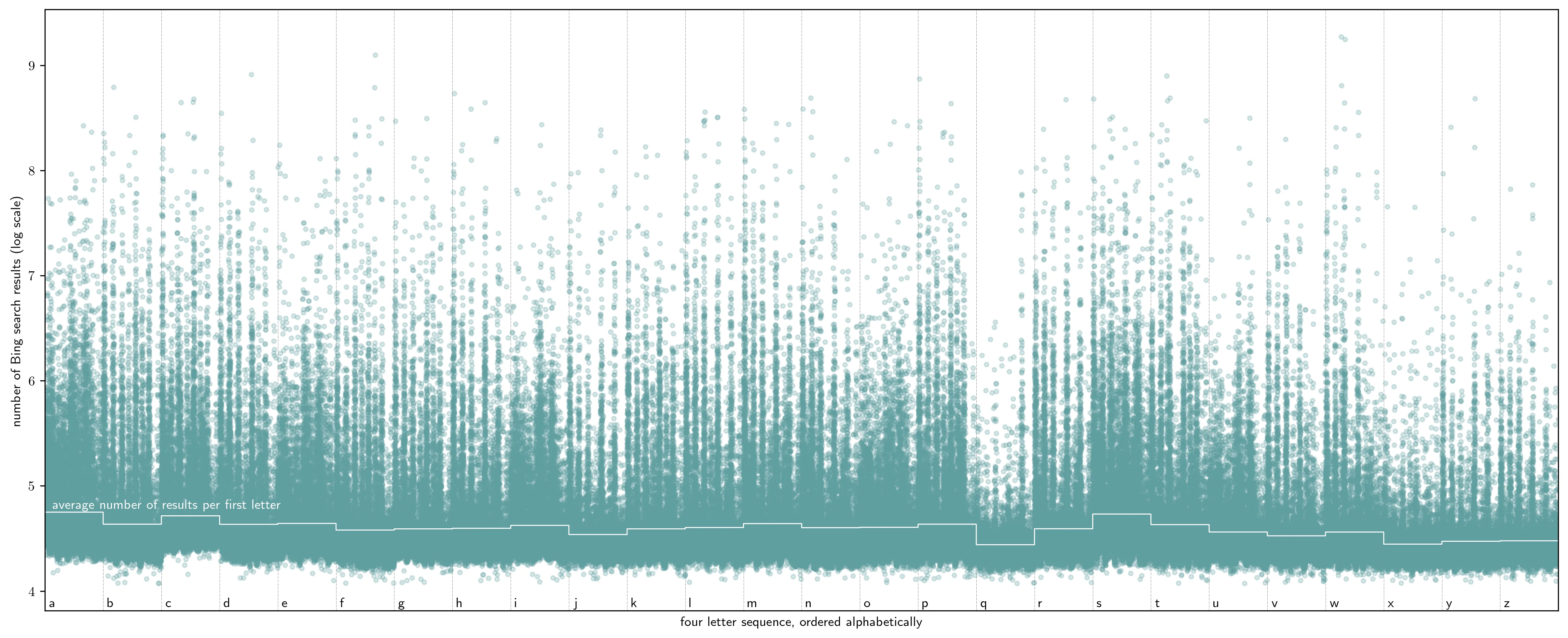

So, I ended up using Bing for this article, which was more generous with allowing automated requests.

User Agents (UAs).

Without reason, some of the cURL requests wouldn’t return parsable HTML. Once again, not an expert in web scraping. However, I did some research and found that realistically spoofing the user agent (UA) of the request can sometimes help. I did this with the help of a python library called fake_useragent, which generates a random UA for each request.

In the above script, we restrict UAs to only those originating on a windows machine, on a guess that maybe Microsoft might like users from their own ecosystem better than others. Have yet to actually test this, though! Additionally, we leverage the functionality of the fake_useragent library analyze real-time prevalence patterns for different UAs, and only utilize UAs in the top 90% of prevalence.

Rate Limiting

I also found that Bing would very quickly block a request if it was part of a session that was making too many requests. So, I implemented a basic semaphore (read: lock) to ensure that only 100 requests could be made at a time.

Time Between Requests.

I also found that, even with UAs, some requests were failing. I hypothesized that this was due to the fact that I was making requests too quickly, and that the search engine was blocking me. So, I added a random sleep time between requests, ranging from 1 to 5 seconds.

Results

I focus all of my analysis on this article on four-letter sequences. However, I will upload the scraped data for three-letter sequences to GitHub along with the rest of the data.

First, I plot the percentile of each sequence in the distribution of number of results. This should show, at a high level, which letters are more and less popular. I see things that are intuitive, yet still interesting to note. Look at words that begin with ‘rare’ letters like Q or X, and you see a noticeable dip in the number of indexed results.

Lastly, I have ChatGPT brainstorm definitions for my 20 lowest-result candidates. To filter, I only keep words with at least 3 pronouncable letter pairs, a heuristic dominated by the presence of at least one vowel in a pair, or the presence of a known English digraph.

| Word | Phonetic Spelling | Definition | Etymology Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iupa | eye-OO-pah | A brief, high-pitched sound, similar to a chirp. | Resembling the structure of onomatopoeic words. |

| Geju | GEH-joo | A small, quick movement or adjustment. | Suggestive of words with Germanic origins describing actions or movements. |

| Yufe | YOO-fay | A light, fluffy material or texture. | Sounds similar to words like ‘fluff’ or ‘puff’. |

| Kuap | KWAP | A quick, snapping closure or fit. | Mimics the sound of something snapping shut. |

| Buub | BOOB | A term for a small, rounded object or shape. | Evokes the roundness implied in words like ‘bubble’. |

| Vuhe | VOO-hay | A gentle, soothing whisper or murmur. | Resembles soft-sounding words. |

| Ujol | OO-jol | A sudden, unexpected turn or twist in a story. | Sounds abrupt, mirroring the nature of the definition. |

| Giuj | GEE-ooge | A quick, bright flash of light. | Sounds sharp and sudden, like a flash. |

| Ihiz | EYE-hiz | A brief, intense feeling of excitement. | Has a zippy, energetic sound. |

| Uvup | OO-vup | A small upward movement or bounce. | Sounds like it has an upward, lifting quality. |

| Mebi | MEH-bee | A term for a moderate, reasonable amount. | Resembles words with a balanced, measured tone. |

| Vuoj | VOO-oj | A swirling, flowing motion, often used to describe water or air. | Evokes the sound of flowing or moving fluid. |

| Iyig | EYE-yig | A quick, darting glance. | Sounds like a quick, sudden action. |

| Yiub | YEE-ub | A playful, teasing remark. | Sounds light-hearted and jovial. |

| Utoj | OO-toj | A small, but significant addition or change. | Sounds like a small tweak or adjustment. |

| Aago | AH-ah-go | A deep, resonant sound. | Evokes the depth and resonance in its pronunciation. |

| Fuob | FOO-ob | A quick, muffled sound. | Sounds soft and somewhat suppressed. |

| Ihuh | EYE-huh | An expression of mild surprise or realization. | Resembles a sudden, instinctive reaction. |

| Vuaf | VOO-af | A swift, slicing motion. | Sounds sharp and swift. |

| Fuuv | FOO-v | A gentle, calming breeze. | Sounds like it carries a soft, flowing quality. |

Discussion

Limitations

There are several limitations to this brief study, of course.

Replicability

I wasn’t able to find much literature on how the number of search results might change with varying user characteristics. I was initially quite worried that, having performed requests from different IP addresses, the results might be skewed. To try and minimize this, I ran all requests (both batch requests and the ones I checked manually) from Cornell’s VPN, which should have fixed me to an Ithaca, NY IP address. Even so, when spot checking my results yesterday, I found that the number of results for a given sequence would be off by as much as ten thousand, especially for requests at the bottom of the number of results distribution.

Another problem with replicability is that the HTML element itself, which I used to parse the number of results, might be eliminated soon. Search engines are rapdily changing their user interfaces as large language models are integrated. Already, I had to spot check around 600 sequences manually, because the HTML element I was using to parse the number of results had been replaced by a hero showing AI generated summaries of the result. I anticipate this will only become more common, and so this analysis might not be replicable in the future.

Search Engine Results are not a perfect proxy for popularity / trademark-ability.

The most obvious limitation is that search engine results are not a perfect proxy for popularity. The indexing algorithms of search engines are largely opaque, and it’s not clear how they determine which results to count. Additionally, an unpopular term might still be trademarked, and a popular term might not be trademarked (or, might not be qualified for trademarking).

Only 3 and 4 letter sequences were considered.

I only considered 3 and 4 letter sequences in this study. This was due, honestly, to being unable to run $26^{(>4)}$ requests successfully. This is an O(N^2) data collection problem, and likely also a O(N^2) analysis problem. I didn’t have to do any analysis on syllables, subwords, etc., largely because the sequences I looked at were so small. Perhaps if this post is interesting, it might be a cool exercise for someone at Google or Bing to run this study for all possible sequences of longer lengths.

Only Bing was used.

I only used Bing for this study, due to the fact that Google aggressively blocks automated requests. It would be interesting to see if the results are similar for Google, or if there are any significant differences.

Only the English alphabet was considered.

I only considered the English alphabet in this study. It would be interesting to see if the results are similar for other languages, or if there are any significant differences.

To Conclude…

I consider this work a utoj. I think I produced a mebi of success in finding sequences that aren’t heavily indexed by the Bing search engine. I created lots of onamonapeas; Iupa! Fuob! Aago! I think the search engine index data I assembled is noisier than I anticipated, and yet I still think this is cool enough to publish. More generally, I think this is an interesting idea — what combinations of letters (especially those that make something pronounceable) are underutilized in daily communication or in the act of naming things?